Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Mon Apr 29, 2013 6:23 pm

HI all,

I'm sure you've seen/heard about that ball turret gunner that was crushed to death upon landing due to mechanical difficulties in getting the turret hatch opened. The B-17 was going down, the gear was stuck. We know the story.

However, was there really no way to rescue the guy? I think about it and can't come up with any solution other than some how doing an air to air transfer of cutting tools to the B17 from another aircraft, possibly a Cub or other light aircraft.

Anyone have ideas? of course, the B17 is low on fuel, engines failing (only 1 left, i recall) clock is ticking...injured men on board, etc....gotta get this turret open quickly!

I'm sure you've seen/heard about that ball turret gunner that was crushed to death upon landing due to mechanical difficulties in getting the turret hatch opened. The B-17 was going down, the gear was stuck. We know the story.

However, was there really no way to rescue the guy? I think about it and can't come up with any solution other than some how doing an air to air transfer of cutting tools to the B17 from another aircraft, possibly a Cub or other light aircraft.

Anyone have ideas? of course, the B17 is low on fuel, engines failing (only 1 left, i recall) clock is ticking...injured men on board, etc....gotta get this turret open quickly!

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Mon Apr 29, 2013 8:19 pm

That was the one off the old Speilberg TV series where he draws the landing gear and it lands on that?

Just pull the Ball Turret Release lever inside the plane, it ejects the ball and the gunner....

Mark H

Just pull the Ball Turret Release lever inside the plane, it ejects the ball and the gunner....

Mark H

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Mon Apr 29, 2013 8:29 pm

You mean this one? http://vimeo.com/56670088

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Mon Apr 29, 2013 11:49 pm

I'm sure Taigh will speak up and correct me, but here goes.

Declutch the turret, and rotate by hand to proper position, Exit gunner.

There already is a rather effective axe on board. And on every airliner you've ever been on, FTM. Use axe to clear any damaged structure keeping you from doing the above.

If that doesn't work, land as gently as possible, on grass where available. The gunner is already in the fetal position, and in the most heavily armoured bit of structure in the airplane. In the event of a crash (minus fire), he's probably in a better place than the waist gunners.

While it's certainly the deep fear of everyone who sees the position, I don't think there are actually many (if any) cases of the gunner being trapped and killed on landing.

Declutch the turret, and rotate by hand to proper position, Exit gunner.

There already is a rather effective axe on board. And on every airliner you've ever been on, FTM. Use axe to clear any damaged structure keeping you from doing the above.

If that doesn't work, land as gently as possible, on grass where available. The gunner is already in the fetal position, and in the most heavily armoured bit of structure in the airplane. In the event of a crash (minus fire), he's probably in a better place than the waist gunners.

While it's certainly the deep fear of everyone who sees the position, I don't think there are actually many (if any) cases of the gunner being trapped and killed on landing.

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 12:11 am

Following on from what Shrike has posted, the story originates with a piece that was written by Andy Rooney, and it has never been backed-up with facts. Those who have tried haven't been able to come up with any facts to support that story (such as bomb group, aircraft, crew, etc.), including the NMUSAF.

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 1:53 am

I don't have any numbers to base it on but I also think it was a rare occurrence but it did happen.

If the ball turret is in the guns straight down position the hatch can open inside the aircraft. If the guns are horizontal then the hatch can open outside the aircraft and theoretically the gunner could bail out if he wore a parachute.

If the turret was just a little off of vertical or horizontal then the hatch is soundly blocked by a big cast aluminum ring structure. The hatch and the surrounding turret casting is about 1/4 to 3/8 inch thick. If the turret and or the surrounding structure was damaged and the turret disabled the gunner could have easily been trapped in the turret. I have no doubt that this happened. If the landing gear was also damaged and could not be lowered then the gunner would most likely die a horrible death.

It would have been difficult to break through with the crash axe carried on board. The other problem was most all of the turret operating mechanism is mounted over the gunner when the guns are in a horizontal position. So just breaking through the turret shell would not free the gunner as you had another 18 inches or more of castings holding hydraulic units, electrical motor, stainless steel ammo boxes (with ammunition) etc to try and hack through.

In the B-24 the turret could be retracted and the bomb hoists were even stowed over the ball turret so that if the hydraulic cylinder, reservoir, pump or hoses were disabled then you could use the bomb hoists to raise the turret. The hoists were strong enough that I think it could have pulled the turret up through damaged surrounding structure. In this case even if the gunner was trapped in the turret at least he could potentially be raised out of harms way. Not so in the B-17.

The ball turret in the B-17 was one of the first things to hit the ground in a belly landing. Of course it would grind and be pushed back and up. Often the turret would tear out the supporting structure on the top of the fuselage and the turret would often depart the aircraft while smashing the turret and fuselage as it did so usually breaking the back of the aircraft so to speak. This was such a problem that the Army Air Force came up with a Technical Order or TO addressing this problem. The plan was to keep a tool kit near the turret to un bolt the turret from the saw horse like mount so it could be dropped free before the belly landing thus preventing damage that might prove to be beyond economical repair. The TO goes on to say that if time permits to remove the K-4 computing gun sight and save it due to its extreme value. There were also placards posted near the turret with the instructions on how to drop the turret.

I have wondered if a gunner was trapped in the turret with the gear stuck up if it might have been better to drop the turret as opposed to landing on the gunner. Possibly attaching chest chutes to the turret and gunner to at least give him a chance. Any way you look at it it's a bleak situation.

I know of one documented case of a gunner being trapped and subsequently dying but it's a bit different. It happened in the 100th BG. They have a painting there at the museum depicting the accident. Here is the story from http://www.truthorfiction.com/rumors/p/piggyback.htm#.UX9azRG9KSM

Piggyback Hero

by Ralph Kinney Bennett

Tomorrow morning they'll lay the remains of Glenn Rojohn to rest in the

Peace Lutheran Cemetery in the little town of Greenock, Pa., just

southeast of Pittsburgh. He was 81, and had been in the air conditioning

and plumbing business in nearby McKeesport. If you had seen him on the

street he would probably have looked to you like so many other graying,

bespectacled old World War II veterans whose names appear so often now

on obituary pages.

But like so many of them, though he seldom talked about it, he could

have told you one hell of a story. He won the Distinguished Flying Cross

and the Purple Heart all in one fell swoop in the skies over Germany on

December 31, 1944.

Fell swoop indeed.

Capt. Glenn Rojohn, of the 8th Air Force's 100th Bomb Group, was flying

his B-17G Flying Fortress bomber on a raid over Hamburg. His formation

had braved heavy flak to drop their bombs, then turned 180 degrees to

head out over the North Sea.

They had finally turned northwest, headed back to England, when they

were jumped by German fighters at 22,000 feet. The Messerschmitt

Me-109s pressed their attack so closely that Capt. Rojohn could see

the faces of the German pilots.

He and other pilots fought to remain in formation so they could use each

other's guns to defend the group. Rojohn saw a B-17 ahead of him burst

into flames and slide sickeningly toward the earth. He gunned his ship

forward to fill in the gap.

He felt a huge impact. The big bomber shuddered, felt suddenly very

heavy and began losing altitude. Rojohn grasped almost immediately that

he had collided with another plane. A B-17 below him, piloted by Lt.

William G. McNab, had slammed the top of its fuselage into the bottom of

Rojohn's. The top turret gun of McNab's plane was now locked in the

belly of Rojohn's plane and the ball turret in the belly of Rojohn's had

smashed through the top of McNab's. The two bombers were almost

perfectly aligned - the tail of the lower plane was slightly to the left

of Rojohn's tailpiece. They were stuck together, as a crewman later

recalled, "like mating dragon flies."

No one will ever know exactly how it happened. Perhaps both pilots had

moved instinctively to fill the same gap in formation. Perhaps McNab's

plane had hit an air pocket.

Three of the engines on the bottom plane were still running, as were all

four of Rojohn's. The fourth engine on the lower bomber was on fire and

the flames were spreading to the rest of the aircraft. The two were losing

altitude quickly. Rojohn tried several times to gun his engines and break

free of the other plane. The two were inextricably locked together.

Fearing a fire, Rojohn cuts his engines and rang the bailout bell. If his

crew had any chance of parachuting, he had to keep the plane under

control somehow.

The ball turret, hanging below the belly of the B-17, was considered by

many to be a death trap - the worst station on the bomber.

In this case, both ball turrets figured in a swift and terrible drama of

life and death.

Staff Sgt. Edward L. Woodall, Jr., in the ball turret of the lower bomber,

had felt the impact of the collision above him and saw shards of metal drop

past him. Worse, he realized both electrical and hydraulic power was gone.

Remembering escape drills, he grabbed the handcrank, released the clutch

and cranked the turret and its guns until they were straight down, then

turned and climbed out the back of the turret up into the fuselage.

Once inside the plane's belly Woodall saw a chilling sight, the ball

turret of the other bomber protruding through the top of the fuselage.

In that turret, hopelessly trapped, was Staff Sgt. Joseph Russo. Several

crewmembers on Rojohn's plane tried frantically to crank Russo's turret

around so he could escape. But, jammed into the fuselage of the lower

plane, the turret would not budge.

Aware of his plight, but possibly unaware that his voice was going out

over the intercom of his plane, Sgt. Russo began reciting his Hail Marys.

Up in the cockpit, Capt. Rojohn and his co-pilot, 2nd Lt. William G.

Leek, Jr., had propped their feet against the instrument panel so they could

pull back on their controls with a ll their strength, trying to prevent

their plane from going into a spinning dive that would prevent the crew

from jumping out.

Capt. Rojohn motioned left and the two managed to wheel the grotesque,

collision-born hybrid of a plane back toward the German coast. Leek felt

like he was intruding on Sgt. Russo as his prayers crackled over the

radio, so he pulled off his flying helmet with its earphones.

Rojohn, immediately grasping that crew could not exit from the bottom of

his plane, ordered his top turret gunner and his radio operator, Tech

Sgts. Orville Elkin and Edward G. Neuhaus, to make their way to the back

of the fuselage and out the waist door behind the left wing.

Then he got his navigator, 2nd Lt. Robert Washington, and his bombardier,

Sgt. James Shirley to follow them. As Rojohn and Leek somehow held the

plane steady, these four men, as well as waist gunner Sgt. Roy Little and tail

gunner Staff Sgt. Francis Chase were able to bail out.

Now the plane locked below them was aflame. Fire poured over Rojohn's

left wing. He could feel the heat from the plane below and hear the sound

of .50 caliber machinegun ammunition "cooking off" in the flames.

Capt. Rojohn ordered Lieut. Leek to bail out. Leek knew that without him

helping keep the controls back, the plane would drop in a flaming spiral

and the centrifugal force would prevent Rojohn from bailing. He refused

the order.

Meanwhile, German soldiers and civilians on the ground that afternoon

looked up in wonder. Some of them thought they were seeing a new Allied

secret weapon - a strange eight-engined double bomber. But anti-aircraft

gunners on the North Sea coastal island of Wangerooge had seen the

collision. A German battery captain wrote in his logbook at 2:47 p.m.:

"Two fortresses collided in a formation in the NE. The planes flew

hooked together and flew 20 miles south. The two planes were unable to fight

anymore. The crash could be awaited so I stopped the firing at these two

planes."

Suspended in his parachute in the cold December sky, Bob Washington

watched with deadly fascination as the mated bombers, trailing black

smoke, fell to earth about three miles away, their downward trip ending

in an ugly boiling blossom of fire.

In the cockpit Rojohn and Leek held g rimly to the controls trying to

ride a falling rock. Leek tersely recalled, "The ground came up faster and

faster. Praying was allowed. We gave it one last effort and slammed into

the ground."

The McNab plane on the bottom exploded, vaulting the other B-17 upward

and forward. It hit the ground and slid along until its left wing slammed

through a wooden building and the smoldering mass of aluminum came to a

stop.

Rojohn and Leek were still seated in their cockpit. The nose of the

plane was relatively intact, but everything from the B-17's massive wings back

was destroyed. They looked at each other incredulously. Neither was badly

injured.

Movies have nothing on reality. Still perhaps in shock, Leek crawled out

through a huge hole behind the cockpit, felt for the familiar pack in his

uniform pocket and pulled out a cigarette. He placed it in his mouth and

was about to light it. Then he noticed a young German soldier pointing a

rifle at him. The soldier looked scared and annoyed. He grabbed the

cigarette out of Leek's mouth and pointed down to the gasoline pouring

out over the wing from a ruptured fuel tank.

Two of the six men who parachuted from Rojohn's plane did not survive

the jump. But the other four and, amazingly, four men from the other

bomber, including ball turret gunner Woodall, survived. All were taken

prisoner. Several of them were interrogated at lengt h by the Germans

until they were satisfied that what had crashed was not a new American

secret weapon.

Rojohn, typically, didn't talk much about his Distinguished Flying Cross.

Of Leek, he said, "In all fairness to my co-pilot, he's the reason I'm

alive today."

Like so many veterans, Rojohn got back to life unsentimentally after the

war, marrying and raising a son and daughter. For many years, though, he

tried to link back up with Leek, going through government records to try

to track him down. It took him 40 years, but in 1986, he found the number

of Leek's mother, in Washington State.

Yes, her son Bill was visiting from California. Would Rojohn like to speak

with him? Two old men on a phone line, trying to pick up some familiar

timbre of youth in each other's voice. One can imagine that first conversation

between the two men who had shared that wild ride in the cockpit of a B-17.

A year later, the two were re-united at a reunion of the 100th Bomb Group

in Long Beach, Calif. Bill Leek died the following year.

Glenn Rojohn was the last survivor of the remarkable piggyback flight.

He was like thousands upon thousands of men -- soda jerks and

lumberjacks, teachers and dentists, students and lawyers and service

station attendants and store clerks and farm boys -- who in the prime of

their lives went to war in World War II. They sometimes did incredible

things, endured awful things, and for the most part most of them pretty

much kept it to themselves and just faded back into the fabric of civilian

life.

Capt. Glenn Rojohn, AAF, died last Saturday after a long siege of illness.

But he apparently faced that fina l battle with the same grim aplomb he

displayed that remarkable day over Germany so long ago. Let us be

thankful for such men.

A great story. I wonder how many more stories like this one are lost

each day as members of the Greatest Generation pass on.

I heard a version of this from the family of the ball turret gunner who said they never knew how their relative had died as there were no details given. They said that they had finally met the pilot who told them the full account. This version says that the pilot and copilot were talking to their ball turret gunner through the intercom all the way to the end.

If the ball turret is in the guns straight down position the hatch can open inside the aircraft. If the guns are horizontal then the hatch can open outside the aircraft and theoretically the gunner could bail out if he wore a parachute.

If the turret was just a little off of vertical or horizontal then the hatch is soundly blocked by a big cast aluminum ring structure. The hatch and the surrounding turret casting is about 1/4 to 3/8 inch thick. If the turret and or the surrounding structure was damaged and the turret disabled the gunner could have easily been trapped in the turret. I have no doubt that this happened. If the landing gear was also damaged and could not be lowered then the gunner would most likely die a horrible death.

It would have been difficult to break through with the crash axe carried on board. The other problem was most all of the turret operating mechanism is mounted over the gunner when the guns are in a horizontal position. So just breaking through the turret shell would not free the gunner as you had another 18 inches or more of castings holding hydraulic units, electrical motor, stainless steel ammo boxes (with ammunition) etc to try and hack through.

In the B-24 the turret could be retracted and the bomb hoists were even stowed over the ball turret so that if the hydraulic cylinder, reservoir, pump or hoses were disabled then you could use the bomb hoists to raise the turret. The hoists were strong enough that I think it could have pulled the turret up through damaged surrounding structure. In this case even if the gunner was trapped in the turret at least he could potentially be raised out of harms way. Not so in the B-17.

The ball turret in the B-17 was one of the first things to hit the ground in a belly landing. Of course it would grind and be pushed back and up. Often the turret would tear out the supporting structure on the top of the fuselage and the turret would often depart the aircraft while smashing the turret and fuselage as it did so usually breaking the back of the aircraft so to speak. This was such a problem that the Army Air Force came up with a Technical Order or TO addressing this problem. The plan was to keep a tool kit near the turret to un bolt the turret from the saw horse like mount so it could be dropped free before the belly landing thus preventing damage that might prove to be beyond economical repair. The TO goes on to say that if time permits to remove the K-4 computing gun sight and save it due to its extreme value. There were also placards posted near the turret with the instructions on how to drop the turret.

I have wondered if a gunner was trapped in the turret with the gear stuck up if it might have been better to drop the turret as opposed to landing on the gunner. Possibly attaching chest chutes to the turret and gunner to at least give him a chance. Any way you look at it it's a bleak situation.

I know of one documented case of a gunner being trapped and subsequently dying but it's a bit different. It happened in the 100th BG. They have a painting there at the museum depicting the accident. Here is the story from http://www.truthorfiction.com/rumors/p/piggyback.htm#.UX9azRG9KSM

Piggyback Hero

by Ralph Kinney Bennett

Tomorrow morning they'll lay the remains of Glenn Rojohn to rest in the

Peace Lutheran Cemetery in the little town of Greenock, Pa., just

southeast of Pittsburgh. He was 81, and had been in the air conditioning

and plumbing business in nearby McKeesport. If you had seen him on the

street he would probably have looked to you like so many other graying,

bespectacled old World War II veterans whose names appear so often now

on obituary pages.

But like so many of them, though he seldom talked about it, he could

have told you one hell of a story. He won the Distinguished Flying Cross

and the Purple Heart all in one fell swoop in the skies over Germany on

December 31, 1944.

Fell swoop indeed.

Capt. Glenn Rojohn, of the 8th Air Force's 100th Bomb Group, was flying

his B-17G Flying Fortress bomber on a raid over Hamburg. His formation

had braved heavy flak to drop their bombs, then turned 180 degrees to

head out over the North Sea.

They had finally turned northwest, headed back to England, when they

were jumped by German fighters at 22,000 feet. The Messerschmitt

Me-109s pressed their attack so closely that Capt. Rojohn could see

the faces of the German pilots.

He and other pilots fought to remain in formation so they could use each

other's guns to defend the group. Rojohn saw a B-17 ahead of him burst

into flames and slide sickeningly toward the earth. He gunned his ship

forward to fill in the gap.

He felt a huge impact. The big bomber shuddered, felt suddenly very

heavy and began losing altitude. Rojohn grasped almost immediately that

he had collided with another plane. A B-17 below him, piloted by Lt.

William G. McNab, had slammed the top of its fuselage into the bottom of

Rojohn's. The top turret gun of McNab's plane was now locked in the

belly of Rojohn's plane and the ball turret in the belly of Rojohn's had

smashed through the top of McNab's. The two bombers were almost

perfectly aligned - the tail of the lower plane was slightly to the left

of Rojohn's tailpiece. They were stuck together, as a crewman later

recalled, "like mating dragon flies."

No one will ever know exactly how it happened. Perhaps both pilots had

moved instinctively to fill the same gap in formation. Perhaps McNab's

plane had hit an air pocket.

Three of the engines on the bottom plane were still running, as were all

four of Rojohn's. The fourth engine on the lower bomber was on fire and

the flames were spreading to the rest of the aircraft. The two were losing

altitude quickly. Rojohn tried several times to gun his engines and break

free of the other plane. The two were inextricably locked together.

Fearing a fire, Rojohn cuts his engines and rang the bailout bell. If his

crew had any chance of parachuting, he had to keep the plane under

control somehow.

The ball turret, hanging below the belly of the B-17, was considered by

many to be a death trap - the worst station on the bomber.

In this case, both ball turrets figured in a swift and terrible drama of

life and death.

Staff Sgt. Edward L. Woodall, Jr., in the ball turret of the lower bomber,

had felt the impact of the collision above him and saw shards of metal drop

past him. Worse, he realized both electrical and hydraulic power was gone.

Remembering escape drills, he grabbed the handcrank, released the clutch

and cranked the turret and its guns until they were straight down, then

turned and climbed out the back of the turret up into the fuselage.

Once inside the plane's belly Woodall saw a chilling sight, the ball

turret of the other bomber protruding through the top of the fuselage.

In that turret, hopelessly trapped, was Staff Sgt. Joseph Russo. Several

crewmembers on Rojohn's plane tried frantically to crank Russo's turret

around so he could escape. But, jammed into the fuselage of the lower

plane, the turret would not budge.

Aware of his plight, but possibly unaware that his voice was going out

over the intercom of his plane, Sgt. Russo began reciting his Hail Marys.

Up in the cockpit, Capt. Rojohn and his co-pilot, 2nd Lt. William G.

Leek, Jr., had propped their feet against the instrument panel so they could

pull back on their controls with a ll their strength, trying to prevent

their plane from going into a spinning dive that would prevent the crew

from jumping out.

Capt. Rojohn motioned left and the two managed to wheel the grotesque,

collision-born hybrid of a plane back toward the German coast. Leek felt

like he was intruding on Sgt. Russo as his prayers crackled over the

radio, so he pulled off his flying helmet with its earphones.

Rojohn, immediately grasping that crew could not exit from the bottom of

his plane, ordered his top turret gunner and his radio operator, Tech

Sgts. Orville Elkin and Edward G. Neuhaus, to make their way to the back

of the fuselage and out the waist door behind the left wing.

Then he got his navigator, 2nd Lt. Robert Washington, and his bombardier,

Sgt. James Shirley to follow them. As Rojohn and Leek somehow held the

plane steady, these four men, as well as waist gunner Sgt. Roy Little and tail

gunner Staff Sgt. Francis Chase were able to bail out.

Now the plane locked below them was aflame. Fire poured over Rojohn's

left wing. He could feel the heat from the plane below and hear the sound

of .50 caliber machinegun ammunition "cooking off" in the flames.

Capt. Rojohn ordered Lieut. Leek to bail out. Leek knew that without him

helping keep the controls back, the plane would drop in a flaming spiral

and the centrifugal force would prevent Rojohn from bailing. He refused

the order.

Meanwhile, German soldiers and civilians on the ground that afternoon

looked up in wonder. Some of them thought they were seeing a new Allied

secret weapon - a strange eight-engined double bomber. But anti-aircraft

gunners on the North Sea coastal island of Wangerooge had seen the

collision. A German battery captain wrote in his logbook at 2:47 p.m.:

"Two fortresses collided in a formation in the NE. The planes flew

hooked together and flew 20 miles south. The two planes were unable to fight

anymore. The crash could be awaited so I stopped the firing at these two

planes."

Suspended in his parachute in the cold December sky, Bob Washington

watched with deadly fascination as the mated bombers, trailing black

smoke, fell to earth about three miles away, their downward trip ending

in an ugly boiling blossom of fire.

In the cockpit Rojohn and Leek held g rimly to the controls trying to

ride a falling rock. Leek tersely recalled, "The ground came up faster and

faster. Praying was allowed. We gave it one last effort and slammed into

the ground."

The McNab plane on the bottom exploded, vaulting the other B-17 upward

and forward. It hit the ground and slid along until its left wing slammed

through a wooden building and the smoldering mass of aluminum came to a

stop.

Rojohn and Leek were still seated in their cockpit. The nose of the

plane was relatively intact, but everything from the B-17's massive wings back

was destroyed. They looked at each other incredulously. Neither was badly

injured.

Movies have nothing on reality. Still perhaps in shock, Leek crawled out

through a huge hole behind the cockpit, felt for the familiar pack in his

uniform pocket and pulled out a cigarette. He placed it in his mouth and

was about to light it. Then he noticed a young German soldier pointing a

rifle at him. The soldier looked scared and annoyed. He grabbed the

cigarette out of Leek's mouth and pointed down to the gasoline pouring

out over the wing from a ruptured fuel tank.

Two of the six men who parachuted from Rojohn's plane did not survive

the jump. But the other four and, amazingly, four men from the other

bomber, including ball turret gunner Woodall, survived. All were taken

prisoner. Several of them were interrogated at lengt h by the Germans

until they were satisfied that what had crashed was not a new American

secret weapon.

Rojohn, typically, didn't talk much about his Distinguished Flying Cross.

Of Leek, he said, "In all fairness to my co-pilot, he's the reason I'm

alive today."

Like so many veterans, Rojohn got back to life unsentimentally after the

war, marrying and raising a son and daughter. For many years, though, he

tried to link back up with Leek, going through government records to try

to track him down. It took him 40 years, but in 1986, he found the number

of Leek's mother, in Washington State.

Yes, her son Bill was visiting from California. Would Rojohn like to speak

with him? Two old men on a phone line, trying to pick up some familiar

timbre of youth in each other's voice. One can imagine that first conversation

between the two men who had shared that wild ride in the cockpit of a B-17.

A year later, the two were re-united at a reunion of the 100th Bomb Group

in Long Beach, Calif. Bill Leek died the following year.

Glenn Rojohn was the last survivor of the remarkable piggyback flight.

He was like thousands upon thousands of men -- soda jerks and

lumberjacks, teachers and dentists, students and lawyers and service

station attendants and store clerks and farm boys -- who in the prime of

their lives went to war in World War II. They sometimes did incredible

things, endured awful things, and for the most part most of them pretty

much kept it to themselves and just faded back into the fabric of civilian

life.

Capt. Glenn Rojohn, AAF, died last Saturday after a long siege of illness.

But he apparently faced that fina l battle with the same grim aplomb he

displayed that remarkable day over Germany so long ago. Let us be

thankful for such men.

A great story. I wonder how many more stories like this one are lost

each day as members of the Greatest Generation pass on.

I heard a version of this from the family of the ball turret gunner who said they never knew how their relative had died as there were no details given. They said that they had finally met the pilot who told them the full account. This version says that the pilot and copilot were talking to their ball turret gunner through the intercom all the way to the end.

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 3:10 am

granted you had to be a little shrimp of small stature for the ball turret position, but I can't imagine a belly gunner "shoe horning" himself in their w/ the bulk of a back pack style chute on & body positioned like a fetus. I was always under the assumption that the belly gunner entered his position sans chute & prayed like crazy!!

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 8:53 am

I believe you're correct..the gunner didn't wear a chute, as there wasn't room in the turret. As for the old story of a trapped gunner being killed in a belly landing, it's looking more and more like an urban legend. When I was taking the restoration shop tour at the NMUSAF some years back, the guide told us that despite exhaustive research their people could find no record of it ever actually happening. In fact, I've been told that so many separate systems would have to be damaged/fail simultaneously in that scenario that it's highly improbable.

SN

SN

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 11:41 am

Steve Nelson wrote:I believe you're correct..the gunner didn't wear a chute, as there wasn't room in the turret. As for the old story of a trapped gunner being killed in a belly landing, it's looking more and more like an urban legend. When I was taking the restoration shop tour at the NMUSAF some years back, the guide told us that despite exhaustive research their people could find no record of it ever actually happening. In fact, I've been told that so many separate systems would have to be damaged/fail simultaneously in that scenario that it's highly improbable.

SN

In the book MASTERS OF THE AIR, the author details a researched account of a belly gunner being crushed. Furthermore, on Andy Rooney's account...he claims he was there...why would he lie?

In either case, the fact that it is reported in the book will probably make it into the HBO/Spielberg mini-series since it's based on the book. They better stop the "urban legend" now before it's too late.

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 12:13 pm

Funny that Spielberg's name should come up in this conversation.

I've always thought that old chestnut about a trapped ball turret gunner came from an old show he wrote and directed way back when. It was called "Amazing Stories" and the episode was "The Mission."

You can watch it for free at the link below. Take note of the remarkable historical accuracy that Spielberg is famous for!

http://vimeo.com/25254900

I've always thought that old chestnut about a trapped ball turret gunner came from an old show he wrote and directed way back when. It was called "Amazing Stories" and the episode was "The Mission."

You can watch it for free at the link below. Take note of the remarkable historical accuracy that Spielberg is famous for!

http://vimeo.com/25254900

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 12:58 pm

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 1:12 pm

I've talked with several B-17 ball turret gunners over the last few years. Although they were usually small in stature, most were not small enough to wear their parachute in the turret and still be able to perform the task at hand. The gunner did have the ability to open the turret hatch and bail out, provided, as Taigh mentioned, the hatch was not blocked by debris or the turret being jammed in the wrong position.

I think I saw a reference to a seat pack 'chute in someone else's post earlier in this thread. B-17 crewmen wore chest pack 'chutes that clipped onto a body harness. The way I understand it, they typically did not wear their 'chutes all the time. They would go get them and put them on when it became necessary.

I think I saw a reference to a seat pack 'chute in someone else's post earlier in this thread. B-17 crewmen wore chest pack 'chutes that clipped onto a body harness. The way I understand it, they typically did not wear their 'chutes all the time. They would go get them and put them on when it became necessary.

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 2:02 pm

I can't even picture a ball turret gunner w/ a chest pack chute maneuvering any easier! re: gun / turret controls, etc. the ball turret gunner couldn't even scratch his ass if he wanted to. it took balls of steel to man that position. what they lacked in height they made up for it in balls hands down.

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 2:30 pm

So many things happened to so many aircraft flying so many missions in WWII that the strangest things did occur. It is documented that it happened in what has to be one of the most bizarre accidents where two B-17's came together and stuck in the 100th BG story above. There are other accounts of it happening as well so to say that this is an urban legend is a bit of revisionist thinking to me. I think that this is one of the worst things that could happen not only to a gunner but for his crew to live with. I would imagine that it is not something that many would talk about.

As for having parachutes in the ball turret it was intended for the crew to wear backpack chutes but it was up to the individual crewmember to decide what he wanted to do. From the ball turret gunners I have talked to it seems that they mostly chose to wear the Quick Attach Harness for the chest pack and had the parachute stowed near the turret inside the fuselage. They planned to get out of the turret, attach their QAC parachute and then exit via the aft entry door.

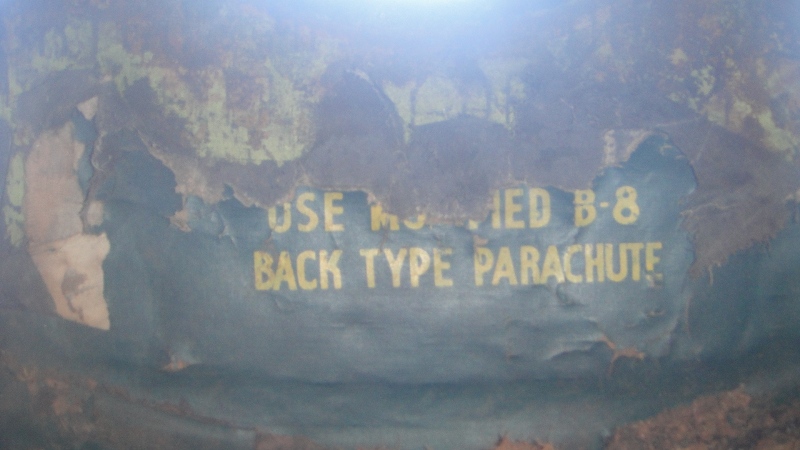

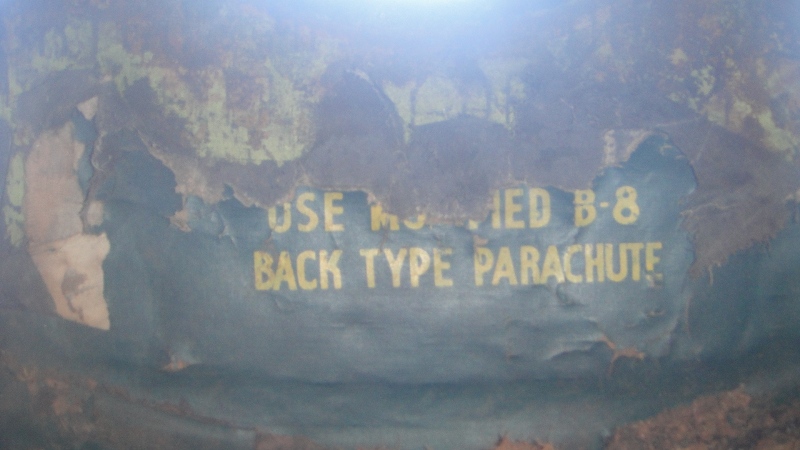

Here is a photo of our ball turret that was new old stock and still had the upholstery in place showing stencilling on the armored seat bottom that the ball turret gunner was capable of having a backpack parachute assuming he was small in stature and could fit.

I fit in a ball turret and I am 6'4". It is actually quite comfortable but I am also not wearing a uniform, heated flying suit, sheepskin flying gear, chute harness etc. At our Gunnery Symposium Wilbur Richardson came up and talked about his experience running the ball turret in flight. He was originally the tail gunner in his B-17's crew. He said their ball turret gunner didn't like the position and he traded places with him. Mr. Richardson was 6'2" and he said that this was the maximum height allowed but there was a specific length of your leg from the hip to the knee that if exceeded would eliminate you from being a ball turret gunner candidate. It's the ammo cans that cause the knee problem here and the later turrets had them mounted externally. These turrets are spacious by comparison.

Some ball turret videos we shot at bomber camp and at the gunnery range are here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LvuChgh4fGg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcPTnsAP9wU

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=l4GS1PND7pA

As for having parachutes in the ball turret it was intended for the crew to wear backpack chutes but it was up to the individual crewmember to decide what he wanted to do. From the ball turret gunners I have talked to it seems that they mostly chose to wear the Quick Attach Harness for the chest pack and had the parachute stowed near the turret inside the fuselage. They planned to get out of the turret, attach their QAC parachute and then exit via the aft entry door.

Here is a photo of our ball turret that was new old stock and still had the upholstery in place showing stencilling on the armored seat bottom that the ball turret gunner was capable of having a backpack parachute assuming he was small in stature and could fit.

I fit in a ball turret and I am 6'4". It is actually quite comfortable but I am also not wearing a uniform, heated flying suit, sheepskin flying gear, chute harness etc. At our Gunnery Symposium Wilbur Richardson came up and talked about his experience running the ball turret in flight. He was originally the tail gunner in his B-17's crew. He said their ball turret gunner didn't like the position and he traded places with him. Mr. Richardson was 6'2" and he said that this was the maximum height allowed but there was a specific length of your leg from the hip to the knee that if exceeded would eliminate you from being a ball turret gunner candidate. It's the ammo cans that cause the knee problem here and the later turrets had them mounted externally. These turrets are spacious by comparison.

Some ball turret videos we shot at bomber camp and at the gunnery range are here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LvuChgh4fGg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcPTnsAP9wU

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=l4GS1PND7pA

Re: Was there really no way to save the ball turret gunner??

Tue Apr 30, 2013 2:55 pm

Taigh, you're really full of it. . . great information, that is! We need to find a way to digitize and download your brain's contents, along with a searchable index.