MIA 10-17-1943 RIP

Fri Oct 17, 2008 9:27 pm

65 years ago Virgil broke off from his flight leader to attack Zero firing on another P-38 and was in turn

shot down by the same Zero. The pilot he died trying to help was Tom McGuire.

His mom, Eva, was a very dear friend of ours.

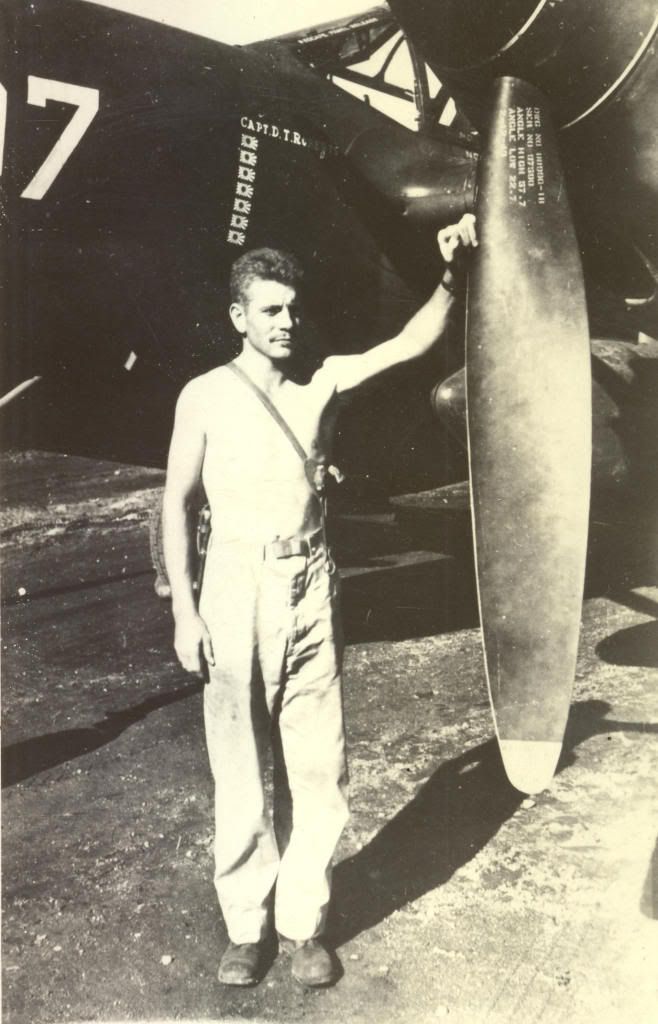

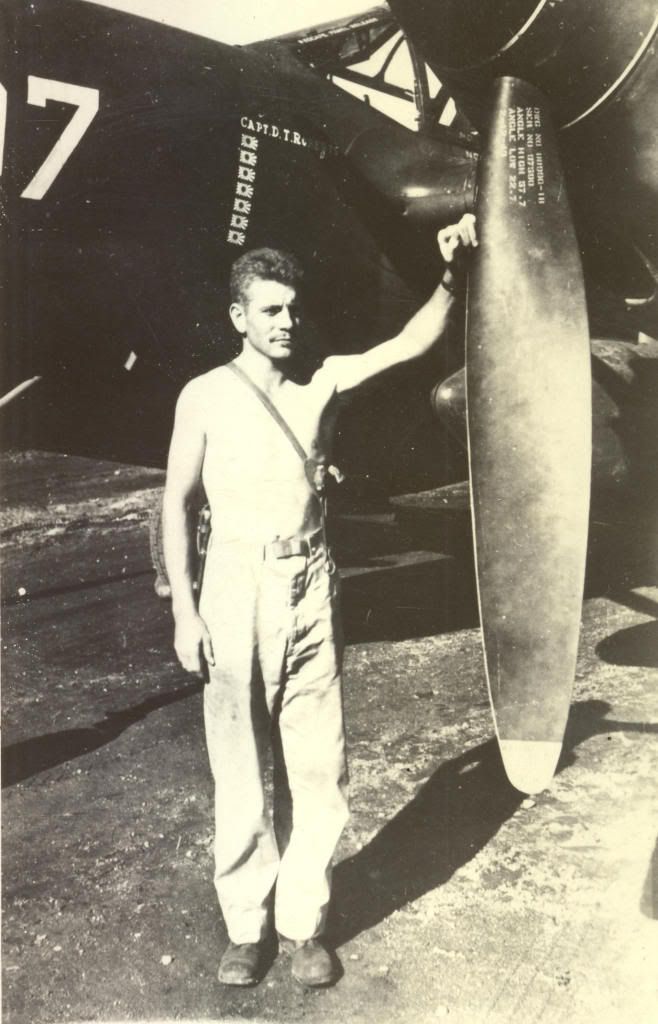

2Lt Virgil Hagan 433rd FS 475th FG Dobodura, NG Oct 17, 1943 MIA/KIA 15 minutes after this photo was taken.

shot down by the same Zero. The pilot he died trying to help was Tom McGuire.

His mom, Eva, was a very dear friend of ours.

2Lt Virgil Hagan 433rd FS 475th FG Dobodura, NG Oct 17, 1943 MIA/KIA 15 minutes after this photo was taken.

Fri Oct 17, 2008 10:31 pm

A true hero. Those are the men that are legends.

Fri Oct 17, 2008 11:55 pm

Standing next to Danny Roberts bird in the photo. Speaking of another forgotten hero.

Thanks for posting this Jack

Dan

Thanks for posting this Jack

Dan

????

Sat Oct 18, 2008 12:15 am

I have the letter Danny Roberts wrote to his mom

???

Sat Oct 18, 2008 12:26 am

The local paper averages one good story every years or so.

Holiday shines light on man’s ultimate sacrifice

by CAPI LYNN Statesman Journal

Lt. Virgil A. Hagan

Age: 22

Unit: 475th Fighter Group, 433rd Fighter Squadron, Army Air Corps

Service: Southwest Pacific during World War II, September 1943 to Oct. 17, 1943. Shot down over Oro Bay, New Guinea, and reported missing in action.

Accomplishments: Flew 21 missions and shot down two enemy planes.

Awards: Awarded an Air Medal with two clusters, a Purple Heart and two Presidential Unit Citations posthumously. Recommended for the Distinguished Flying Cross but paperwork was lost.

Stories about the lives of soldiers who have died in the war against Iraq fill pages of today’s newspapers.

Tales about the families left behind dominate television news broadcasts.

But years ago, little space or time was devoted to those who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

People such as Virgil Hagan were memorialized by their loved ones but few others.

“I think he’s just been forgotten,” local aviation historian Jack Cook said, “and that’s the real tragedy.”

Today, the World War II pilot will be remembered by Cook and by Hagan’s family, including three siblings who live in the Willamette Valley.

Memorial Day is a time to remember people who sacrificed their lives, including the 17 servicemen from Oregon who have died the past year in Iraq and the thousands before them who never came home.

Virgil Hagan graduated from Salem High School in 1940. He was described as a typical teenager who competed in wrestling, boxing and track.

“I think he was just mediocre,” Eugene’s John Hagan said of his brother’s athletic endeavors.

Sister Julie Cummings described Virgil as a genuinely nice guy.

“I don’t remember ever fighting with him,” the 78-year-old Salem woman said. “I guess I always thought he was pretty special.”

Not long after high school, Virgil joined the Oregon Army National Guard as a medic. He was stationed at Fort Stevens on June 21, 1942, when a Japanese submarine fired on installations.

No damage was sustained, and the fort commander refused to allow return fire.

Virgil decided then and there that he wanted to fight the war in the air, not on the ground. He applied and was accepted to flight school, receiving his wings and commission less than a year later.

He was assigned to the 475th Fighter Group, 433rd Fighter Squadron.

Before leaving, he broke off the engagement with his fiancée and said a special goodbye to his mother.

“I think he knew he wasn’t going to come back,” said Cook, who has done exhaustive research about Virgil Hagan and his family.

Fearless flyer

Lt. Hagan was sent to Dobodura, the advanced Allied base on New Guinea. His squadron entered combat in September 1943, not long after his 22nd birthday.

He flew a P-38 Lightning, one of the most advanced and versatile combat planes used during World War II.

The P-38 was noted for its speed (greater than 400 miles per hour), awesome firepower (20-mm nose cannon supplemented by four .50-caliber machine guns) and rugged, heavily armored construction.

None of that technology ultimately was able to protect Virgil, who was regarded as a highly aggressive and fearless pilot.

He was credited with flying 21 missions and shooting down two enemy planes in just a month and a half before he was reported missing.

Cook met Hagan’s flight leader years later and was told that Virgil was the only wing man he ever lost in the war.

“Even 50, 60 years later, he felt tremendous guilt over that,” Cook said. “But he told me that he knew Virgil wasn’t going to make it.

“There were five pilots all from the same flight class who were very aggressive, and all of them were killed.”

Missing in action

The Japanese were attacking Oro Bay, which the Allies used for shipping supplies, when Hagan and his squadron were called in for support Oct. 17, 1943.

The family knows few details about the circumstances that led to Virgil’s death.

“All that I heard was he was diving on a Japanese Zero and went into a cloud, and that was the last ever seen of him,” John said. “There was a lot of water in the area and a bunch of islands. They searched for him for quite a while and couldn’t even find an oil slick on the water.”

From what Cook has learned, Hagan’s group of four planes was pursuing dive bombers.

Hagan was said to have left his group to go to the aid of another pilot when he was shot down. That pilot, whom Hagan might have helped save, also was shot down but later was rescued.

His name: Thomas McGuire.

McGuire went on to become the No. 2 ace for the United States with 38 victories and was awarded the Medal of Honor. McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey is named after him.

Hagan is thought to have been shot down by Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, who many consider Japan’s top ace. Nishizawa, who was credited with shooting down about 100 planes, was killed in action about a year later above the Philippines.

News hits home

The day after Hagan was reported missing in action, a short story ran on an inside page of the Capital Journal, noting that Hagan had gunned down an enemy plane. The delayed report actually referred to his efforts the day before he went down.

It wasn’t until Oct. 27 that the newspaper reported Hagan was missing, with a three-paragraph item on the front page and a small photograph.

The family originally was informed by Western Union telegraph. Cummings, who was about 17 at the time, also remembers officials coming to their house on Cottage Street NE.

“I think the minister and somebody from the service came to let us know,” she said. “I happened to be over at the neighbor girl’s at the time, and they called me to come home.”

John Hagan, 18 at the time, received the news in Missoula, Mont., where he was attending pre-flight school training.

His mother confided in Cook years later that she made calls to the military begging that John would not have to serve overseas after finishing flight school.

She desperately wanted to protect her only other son.

Fortunately for her, the war ended about the time John received his wings and was awaiting orders. John then opted for an early-out with the Army Air Corps and went on to serve a lengthy career in the Army National Guard.

Dear Virgil

Virgil’s mother, Eva Hagan, continued to write him letters after he was declared MIA, signing them “Love, Mama.”

Most of them wound up back in her mailbox, stamped “returned to sender.”

She kept them bound with string and later gave the 4-inch stack to Cook, who befriended her in the late 1980s.

“They never gave up hope that he was alive,” Cook said. “It’s really sad to read the letters.

“They kept writing into the middle of ’44 before they finally gave up.”

Eva, who died almost five years ago at age 98, gave several photographs, documents and other letters to Cook for safekeeping.

“Before I met Eva, you didn’t read about the aftermath and what these families go through,” Cook said. “Maybe that was her gift to me, that it wasn’t all glory and adventure.”

Among the memorabilia Cook has is a letter from Virgil to his folks dated Oct. 16, the day before he was shot down.

“We really had a glorious day here yesterday,” he wrote in legible cursive. “About 60 to 70 Japanese Zeros & dive bombers came in near here for shipping yesterday, and we really showed them a bad time.”

He complained about another pilot taking credit for a victory — shooting down an enemy plane — when he felt he had put “as much lead or more into him.”

Later in the letter he gave a detailed account of one of his victories and wrote: “I got that first one for your father.”

In closing, Virgil mentioned that he had sent $150 home, including $10 for a wedding present for his brother and $5 for a birthday present for one of his sisters.

Footnote in history

For Cook, researching the story of Virgil Hagan became personal after Eva entrusted him with all that was left of her son.

He shared one of the photographs — of the young, shirtless pilot leaning against the propeller of a grounded plane less than 20 minutes before he was shot down — with the author of “Possum, Clover & Hades: The 475th Fighter Group in World War II.”

Hagan was with the Possum squadron and is noted in the back in a long list of pilots who served with the 475th, one of the highest-scoring fighter units in the southwest Pacific.

“There are so many famous pilots and aces in this group,” Cook said, “some kid from Salem that was killed within a month and a half of going over there, he’s lucky to get two sentences.”

Time to remember

The family is thankful for all the research Cook has done. Mike Hagan expects that if not for him, many of the details of his uncle’s World War II service would have been lost by now.

“I definitely regret the fact that I never had the opportunity to meet him,” said Mike, a member of Detachment 1, Company D, 113th Aviation in Pendleton.

Mike followed in the footsteps of his father, John, and has made a career out of the National Guard.

Today, as many Americans take time to honor the men and women who have died serving their country, a few will pause to remember the sacrifice of a 22-year-old pilot from Salem who never came home.

There is no gravesite for Virgil’s family to decorate with flowers. His name is inscribed on the Wall of the Missing at Manila on the Philippine Islands.

“We don’t particularly talk about him too much,” Cummings said, “but we will always remember him.”

Holiday shines light on man’s ultimate sacrifice

by CAPI LYNN Statesman Journal

Lt. Virgil A. Hagan

Age: 22

Unit: 475th Fighter Group, 433rd Fighter Squadron, Army Air Corps

Service: Southwest Pacific during World War II, September 1943 to Oct. 17, 1943. Shot down over Oro Bay, New Guinea, and reported missing in action.

Accomplishments: Flew 21 missions and shot down two enemy planes.

Awards: Awarded an Air Medal with two clusters, a Purple Heart and two Presidential Unit Citations posthumously. Recommended for the Distinguished Flying Cross but paperwork was lost.

Stories about the lives of soldiers who have died in the war against Iraq fill pages of today’s newspapers.

Tales about the families left behind dominate television news broadcasts.

But years ago, little space or time was devoted to those who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

People such as Virgil Hagan were memorialized by their loved ones but few others.

“I think he’s just been forgotten,” local aviation historian Jack Cook said, “and that’s the real tragedy.”

Today, the World War II pilot will be remembered by Cook and by Hagan’s family, including three siblings who live in the Willamette Valley.

Memorial Day is a time to remember people who sacrificed their lives, including the 17 servicemen from Oregon who have died the past year in Iraq and the thousands before them who never came home.

Virgil Hagan graduated from Salem High School in 1940. He was described as a typical teenager who competed in wrestling, boxing and track.

“I think he was just mediocre,” Eugene’s John Hagan said of his brother’s athletic endeavors.

Sister Julie Cummings described Virgil as a genuinely nice guy.

“I don’t remember ever fighting with him,” the 78-year-old Salem woman said. “I guess I always thought he was pretty special.”

Not long after high school, Virgil joined the Oregon Army National Guard as a medic. He was stationed at Fort Stevens on June 21, 1942, when a Japanese submarine fired on installations.

No damage was sustained, and the fort commander refused to allow return fire.

Virgil decided then and there that he wanted to fight the war in the air, not on the ground. He applied and was accepted to flight school, receiving his wings and commission less than a year later.

He was assigned to the 475th Fighter Group, 433rd Fighter Squadron.

Before leaving, he broke off the engagement with his fiancée and said a special goodbye to his mother.

“I think he knew he wasn’t going to come back,” said Cook, who has done exhaustive research about Virgil Hagan and his family.

Fearless flyer

Lt. Hagan was sent to Dobodura, the advanced Allied base on New Guinea. His squadron entered combat in September 1943, not long after his 22nd birthday.

He flew a P-38 Lightning, one of the most advanced and versatile combat planes used during World War II.

The P-38 was noted for its speed (greater than 400 miles per hour), awesome firepower (20-mm nose cannon supplemented by four .50-caliber machine guns) and rugged, heavily armored construction.

None of that technology ultimately was able to protect Virgil, who was regarded as a highly aggressive and fearless pilot.

He was credited with flying 21 missions and shooting down two enemy planes in just a month and a half before he was reported missing.

Cook met Hagan’s flight leader years later and was told that Virgil was the only wing man he ever lost in the war.

“Even 50, 60 years later, he felt tremendous guilt over that,” Cook said. “But he told me that he knew Virgil wasn’t going to make it.

“There were five pilots all from the same flight class who were very aggressive, and all of them were killed.”

Missing in action

The Japanese were attacking Oro Bay, which the Allies used for shipping supplies, when Hagan and his squadron were called in for support Oct. 17, 1943.

The family knows few details about the circumstances that led to Virgil’s death.

“All that I heard was he was diving on a Japanese Zero and went into a cloud, and that was the last ever seen of him,” John said. “There was a lot of water in the area and a bunch of islands. They searched for him for quite a while and couldn’t even find an oil slick on the water.”

From what Cook has learned, Hagan’s group of four planes was pursuing dive bombers.

Hagan was said to have left his group to go to the aid of another pilot when he was shot down. That pilot, whom Hagan might have helped save, also was shot down but later was rescued.

His name: Thomas McGuire.

McGuire went on to become the No. 2 ace for the United States with 38 victories and was awarded the Medal of Honor. McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey is named after him.

Hagan is thought to have been shot down by Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, who many consider Japan’s top ace. Nishizawa, who was credited with shooting down about 100 planes, was killed in action about a year later above the Philippines.

News hits home

The day after Hagan was reported missing in action, a short story ran on an inside page of the Capital Journal, noting that Hagan had gunned down an enemy plane. The delayed report actually referred to his efforts the day before he went down.

It wasn’t until Oct. 27 that the newspaper reported Hagan was missing, with a three-paragraph item on the front page and a small photograph.

The family originally was informed by Western Union telegraph. Cummings, who was about 17 at the time, also remembers officials coming to their house on Cottage Street NE.

“I think the minister and somebody from the service came to let us know,” she said. “I happened to be over at the neighbor girl’s at the time, and they called me to come home.”

John Hagan, 18 at the time, received the news in Missoula, Mont., where he was attending pre-flight school training.

His mother confided in Cook years later that she made calls to the military begging that John would not have to serve overseas after finishing flight school.

She desperately wanted to protect her only other son.

Fortunately for her, the war ended about the time John received his wings and was awaiting orders. John then opted for an early-out with the Army Air Corps and went on to serve a lengthy career in the Army National Guard.

Dear Virgil

Virgil’s mother, Eva Hagan, continued to write him letters after he was declared MIA, signing them “Love, Mama.”

Most of them wound up back in her mailbox, stamped “returned to sender.”

She kept them bound with string and later gave the 4-inch stack to Cook, who befriended her in the late 1980s.

“They never gave up hope that he was alive,” Cook said. “It’s really sad to read the letters.

“They kept writing into the middle of ’44 before they finally gave up.”

Eva, who died almost five years ago at age 98, gave several photographs, documents and other letters to Cook for safekeeping.

“Before I met Eva, you didn’t read about the aftermath and what these families go through,” Cook said. “Maybe that was her gift to me, that it wasn’t all glory and adventure.”

Among the memorabilia Cook has is a letter from Virgil to his folks dated Oct. 16, the day before he was shot down.

“We really had a glorious day here yesterday,” he wrote in legible cursive. “About 60 to 70 Japanese Zeros & dive bombers came in near here for shipping yesterday, and we really showed them a bad time.”

He complained about another pilot taking credit for a victory — shooting down an enemy plane — when he felt he had put “as much lead or more into him.”

Later in the letter he gave a detailed account of one of his victories and wrote: “I got that first one for your father.”

In closing, Virgil mentioned that he had sent $150 home, including $10 for a wedding present for his brother and $5 for a birthday present for one of his sisters.

Footnote in history

For Cook, researching the story of Virgil Hagan became personal after Eva entrusted him with all that was left of her son.

He shared one of the photographs — of the young, shirtless pilot leaning against the propeller of a grounded plane less than 20 minutes before he was shot down — with the author of “Possum, Clover & Hades: The 475th Fighter Group in World War II.”

Hagan was with the Possum squadron and is noted in the back in a long list of pilots who served with the 475th, one of the highest-scoring fighter units in the southwest Pacific.

“There are so many famous pilots and aces in this group,” Cook said, “some kid from Salem that was killed within a month and a half of going over there, he’s lucky to get two sentences.”

Time to remember

The family is thankful for all the research Cook has done. Mike Hagan expects that if not for him, many of the details of his uncle’s World War II service would have been lost by now.

“I definitely regret the fact that I never had the opportunity to meet him,” said Mike, a member of Detachment 1, Company D, 113th Aviation in Pendleton.

Mike followed in the footsteps of his father, John, and has made a career out of the National Guard.

Today, as many Americans take time to honor the men and women who have died serving their country, a few will pause to remember the sacrifice of a 22-year-old pilot from Salem who never came home.

There is no gravesite for Virgil’s family to decorate with flowers. His name is inscribed on the Wall of the Missing at Manila on the Philippine Islands.

“We don’t particularly talk about him too much,” Cummings said, “but we will always remember him.”

Sat Oct 18, 2008 2:39 am

Dan Johnson II wrote:Standing next to Danny Roberts bird in the photo. Speaking of another forgotten hero.

Thanks for posting this Jack

Dan

We haven't forgotten.

Sat Oct 18, 2008 6:03 am

Sat Oct 18, 2008 6:03 am

ZeamerB17 wrote:Dan Johnson II wrote:Standing next to Danny Roberts bird in the photo. Speaking of another forgotten hero.

Thanks for posting this Jack

Dan

We haven't forgotten.

And never will......

Lynn